Democrats Keep Learning the Wrong Lessons From Their Victories

The latest "victory" being Mamdani's NYC Mayoral Primary win

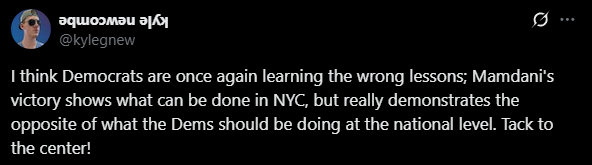

Once again, New York City politics have become a national conversation that political addicts such as myself can’t look away from. Three years ago I wrote about Mayor Eric Adams’ fight to reopen schools in the city amidst the omicron wave, and now I’m back because Zohran Mamdani’s mayoral primary victory has national Democratic leaders learning the exact wrong lessons. As I said this morning on X:

This continues a long running trend of Democrats learning the wrong lessons from their election, legislative, and judicial victories. This is a phenomenon that Jeremiah Johnson described extremely well over on his blog, Infinite Scroll, in a post on how Democratic activists’ tactics have been hindered by learning the wrong lessons from the fight for gay marriage. I highly encourage you to read his piece, but the TL;DR is that gay marriage was unique as an issue in that it was maximalist (it made sense not to accept any compromises), it was costless (all that was changing was the letter of the law), and it was moral (equality was the explicit and only goal). While these features do indeed describe gay marriage as a cause, they are just not applicable to very many other issues.

So when Democratic activists tried to slap maximalist and moral rhetoric on an issue like student loan debt forgiveness during the Biden administration while eschewing the costs and trying to claim it was a costless issue, you can see why there was pushback. Not only was student loan forgiveness not free, it would shift the payback burden from individuals to the American tax base writ large, which of course includes many people who never went to college and earn less money than college graduates. Just imagine for a second that as a high school graduate you wanted to attend college, but couldn’t for some reason, maybe personal or financial. Now imagine that years later, college-educated leftists online are screaming to you, a GED holder who makes less money than they do, that your tax dollars should help completely pay off their student loans because it’s the right thing to do. Doesn’t sound like a moral victory to me.

A scenario like this really helps explain why working-class voters increasingly voted for Trump in 2024, and why Democrats are now seen as the party of scolds. Despite what many Democratic activists would have you believe, weighing trade-offs is not bigotry. When activists are pushing for policy that will cost tens of billions of dollars, maximalism just isn’t the right approach. Compromise should be a logical endpoint, not an impossibility.

This brings us back to NYC and Mamdani.

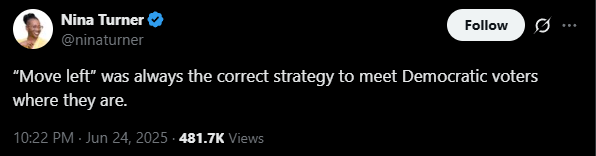

After his rather last-minute upset victory over Andrew Cuomo in the Democratic mayoral primary, a lot of the leftist reaction online looked something like this:

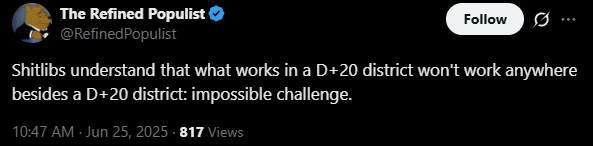

But here’s the problem: this is just maximalism all over again, but painted across the entire Democratic platform rather than a single issue. The consequences are obvious; policies that might be popular enough to win a Democratic primary in NYC will not work on the national level. While the tweet below is rather crass, I think it’s directionally correct about where the Democratic party is right now:

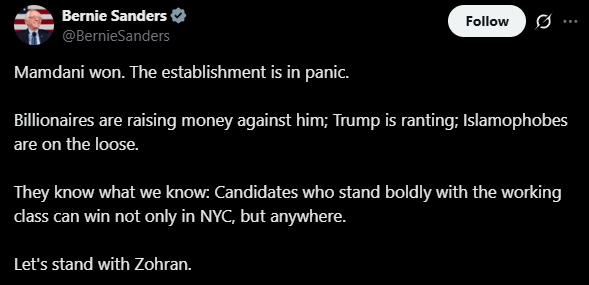

Even ignoring specific political parties, voters often have very different ideas of what they want to see politically at the municipal vs national levels. Even on the best of days, you can’t draw a straight line between popular municipal and national policies. That’s why I get concerned when national Democratic figures such as Bernie Sanders say something like this:

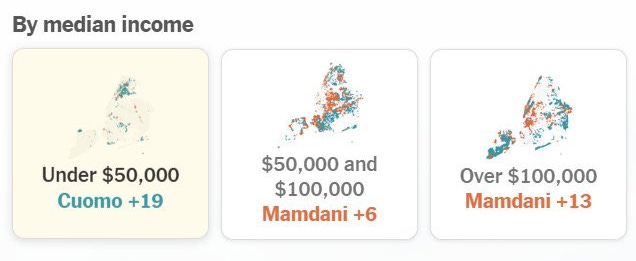

The biggest problem with Bernie’s characterization of Mamdani’s victory is that Mamdani lost the lowest income earners to Cuomo by NINETEEN points. Not exactly a working-class sweep.

The lesson from Mamdani’s victory isn’t to move further left. It isn’t to continue positioning yourselves as the party of the working class while working class voters continue to flee. It isn’t to keep moralizing every leftist pet issue. The actual lessons are much different, and a bit more nuanced.

Lesson one for national Democrats to take away from Mamdani’s victory is the continued importance of the ground game. Say what you want about Mamdani, but he ran an impressive campaign. With an army of volunteers and a goal to knock on one million doors (they actually did 1.5m!), Mamdani’s team also made effective use of technology to track their campaigning progress. There was a lot of talk during the 2024 election cycle about the purported strength of Kamala Harris' ground game. After a decisive Trump victory that included Harris losing each and every swing state, multiple outlets bemoaned how the ground game didn’t make a difference. What Mamdani shows us is that the ground game does still matter, and does influence campaign outcomes. While this is one of many campaign strategies that doesn’t translate 1:1 from the municipal to the national level, there’s still plenty to learn from Mamdani’s on-the-ground presence.

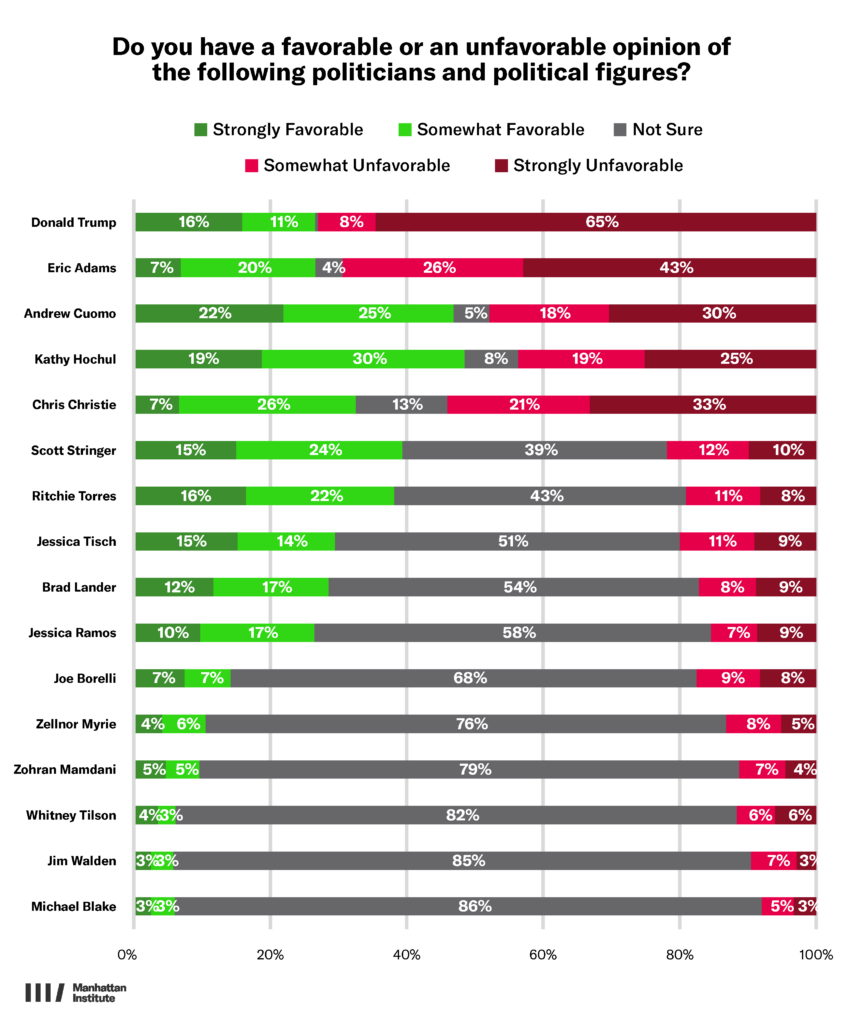

Lesson two is to not be afraid of new names. Mamdani emerged from the New York State Assembly backwater earlier this year, and quickly rose to prominence. In polling conducted at the end of January, 79% of NYC voters polled were “unsure” of their opinion of Mamdani (see below), a.k.a. the vast majority of that 79% had no idea who he was. Disruption is good, actually, and Mamdani has demonstrated how new (and younger!) faces can get voters engaged. National Democrats actually had this largely right back in the early days of the Obama campaign, but they forgot that lesson during the 2016 primary when Hillary Clinton won over Bernie Sanders. The part of Bernie’s tweet above that I 100% agree with is that disruption of the Democratic establishment is a good thing. The Democrats have a product that isn’t selling the same way it used to, and a change in advertising can only get you so far. Sometimes you need to change the product itself to better compete. Andrew Cuomo is the perfect allegory for this; he rolled into the primary as an established Democrat hoping to coast off name recognition and support for Israel. With that as his main opposition, Mamdani was able to adjust on the fly and overcome Cuomo with brute force.

The third and most important lesson for Democrats from this turn of events is that they should be malleable. The most impressed I’ve been with Mamdani so far is when he explicitly talked about issues he’s changed his mind on. A poignant example appears in an interview he did with the New York Times, where he mentioned how he now recognizes the importance of private developers in addressing NYC’s housing crisis. For a politician that’s been described as socialist, this is a sea change in policy that successfully tacks back to the center. Democrats need to do this more, not less, if they want to succeed nationally. Change unpopular policies. Acknowledge mistakes. Be human. Voters will appreciate it.

What I now want to underscore here is that I’m actually no particular fan of Mamdani’s. In the past, he has supported extremist ideas such as defunding the police, though he has since walked some of those views back (making use of lesson three!). While he may have distanced himself from some 2020-era “progressive” policies, his current platform is still a wild card, with overtly socialist policies such as government-run stores and rent freezes very much on the agenda. With that said, you’re probably wondering: if I’m no fan of Mamdani’s, why do I seem to care how effective the Democratic Party is?

The better question is, who doesn’t? With a strong Democratic Party, all of a sudden politics becomes a lot more competitive and both parties have to really put forth their best effort. This brings me to what I call the Free Market Theory of Politics: as with goods and services, more competition between political parties ultimately breeds a better product for the consumer (the voter, in this case). While the U.S. is at a perennial disadvantage in this area thanks to the entrenched duopolistic system, there is still plenty of room for more competition between the two players in the American political market.

If national Democrats learn the correct lessons from their victories and begin tacking back to the center (the exact wrong takeaway from Mamdani’s victory would be to run someone like him at the national level right now), all of a sudden the Republicans have to start doing the same lest they start bleeding representation. For some time now, the two parties have been in a race to see who can get further from the center; this has largely spelled the end for bipartisanship, and has polarized even the most banal issues. That’s not to absolve many individual politicians of responsibility for helping create and foster this hostile environment, but the reason they were able to do that so effectively is that the parties were already drifting apart.

A mass movement back to the center is what is needed here, and it only takes one party to get it started. As I wrote four years ago in a piece about Liberaltarianism:

Thankfully, these problems of hyper-partisanship and voter disenfranchisement have a very simple solution: a mass movement towards the center. Centrism is quite literally the definition of balance; at the center there are elements of all political ideologies in varying balances depending on who you are. In my opinion, what politics should equate to in the end is a group of centrist parties with different balances of the four Nolan chart ideologies as their platforms. Voters will choose the balance that most matches their own, and the party that garners the most support will legitimately represent the most popular perspectives and values in the society the voters are a part of.

The one thing that Democrats can do to really scare Republicans is to become the most effective political fighting force they can be. Shed the extremism, get some new and younger faces to the forefront (probably not David Hogg, though), and find a way to win market share, not just mind share. Doing so will result in a better political product for everyone, and who knows, they might even win a few more elections along the way.